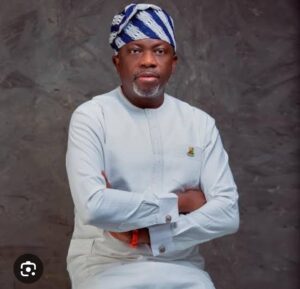

Mr Ọlawale Ajao is a journalist and founder of Omo Yoruba Atata Socio-cultural Initiative (ỌYÀSI), registered under the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC) to showcase and promote Yoruba cultural values globally. In December 28, 2024, the group hosted it’s maiden World Headdress Day in Ibadan, the Oyo State capital, and went home with a modest and inspiring success. Ajao, in this interview with The Tabloid.net, explains issues regarding the group and his bond with Yoruba cultural heritage. Excerpts:

What is your World Headdress Day out to achieve?

The celebration aims to sportlight the vibrant diversity of headdresses from cultures across the globe while championing the recognition of World Headdress Day by UNESCO. At our maiden edition, we had a good number of participants from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds donning symbolic Headdresses that represent their heritage.

Have you ever worn shirts and trausers because I never ever saw you in any?

Yes, I used to wear them.

When did you stop wearing them?

I stopped wearing non-native attire in 2008. I gave them out one by one until I was left with none. I had actually started wearing traditional attire in 2006, beginning with bùbá and sọ́ọ́rọ́, but since I was just starting out, I didn’t have many. So, I wore them intermittently until I gradually replaced all my shirts and trousers with Yorùbá cultural attires. Do you know the irony of it, Sir? As culturally inclined as ALÁRÒYÈ Newspaper organisation is, I thought the consistent adornment of native attire would be welcomed there—but alas! During my first year in the organisation as an Industrial Trainee, the then editor, the late Chief Tade Dairo of blessed memory, arrived at the office one morning and said to me:

“Ṣé búbà àti ṣọ́ọ́rọ́ lo fẹ́ẹ́ máa wọ̀ wá sọ́fíìsì lójoojúmọ́ ni? Àwa kì í múra báyìí l’Ékòó. Tí a bá rán ẹ jáde, tí o bá fẹ́ẹ́ wọ bọ́ọ̀sì, eléyìí kò ní í jẹ́ kí o lè sáré gán bọ́ọ̀sì.”

That was how I was barred from consistently wearing búbà and sọ́ọ́rọ́ at the time. However, that was his personal opinion, not the stance of the management, because all members of the management team admire Yorùbá culture and are true promoters of it.

When were you employed officially?

I became a staff reporter at ALÁRÒYÈ immediately after completing my Industrial Training in 2007, by which time a new editor had taken over. I was immediately posted to Ibadan as the Oyo State Correspondent. That was when I decided to adopt dàǹṣíkí and kẹ̀ǹbẹ̀ with the abetíajá cap. By 2008, I had completely replaced all my attires—including bùbá and sọ́ọ́rọ́—with only dàǹṣíkí and kẹ̀ǹbẹ̀ paired with abetíajá.

Which schools did you attend?

I attended three primary schools: AUD Primary School, Arárọ̀mí; Islamic Mission Primary School, Olósìí; and DC School, Olúkọ̀tún—all in Iwo, Osun State. For my secondary education, I attended St. Anthony’s Catholic Grammar School, Olúkọ̀tún, before transferring to Anwar-Ul-Islam Grammar School, both in Iwo.

Your tertiary education?

I began my tertiary education at the Federal Polytechnic, Offa, Kwara State, where I earned an OND in Mass Communication. After that, I attended the International Institute of Journalism, where I obtained a Higher Diploma in Journalism. It was only after this that I proceeded to the University of Ibadan, where I earned both a BA and an MA in Yorùbá.

What are the challenges you face due to your appearance in Yoruba attires?

There were a few challenges, but I saw them as mere encouragement to strengthen my determination to promote the culture because I am an avowed advocate of Yorùbá culture and African tradition. This style of dressing was not as common before 2007 as it is now—it was rare to see people wearing it. I don’t think there was anyone who consistently wore dàǹṣíkí and abetíajá except for babaláwos, drummers, and undertakers—and even then, only while at work. Since no one as young as I was dressed in dàǹṣíkí, kẹ̀ǹbẹ̀, and abetíajá, it seemed strange to many people. Some called me all sorts of names, such as “Babaláwo!” and “Undertaker!” Some would even greet me with “Àbọrúbọyè o” as if I were a traditional priest. Others, out of disdain, deliberately referred to me as an undertaker.

In fact, some people believed my commitment to this style of dressing would prevent me from finding a wife. Out of concern, some advised me to diversify my wardrobe—to wear jeans and a top or a shirt and trousers sometimes instead of donning dàǹṣíkí, kẹ̀ǹbẹ̀, and abetíajá all the time. They insisted that no lady would want to marry someone so deeply rooted in culture, especially since I also have tribal marks on my face.

But I thank God that this “ugly man” finally found a kind-hearted woman who chose to marry him.

How did this happen?

When I was about to introduce myself to my fiancée’s parents in Lagos, my close friend advised me to wear anything but my usual dàǹṣíkí. He reasoned that Lagos was not a place where Yorùbá culture was widely embraced and admired. He warned that if I insisted on wearing my traditional attire, I might lose my fiancée.

What was your reaction to this threat?

As an unwavering advocate of Yoruba culture, I defied all warnings and went to meet her parents just as I was. To my surprise, they liked my attire. As if her parents were present when my friend was advising me against dressing traditionally and speaking pure Yorùbá. After about an hour of conversation, my fiancée’s father looked at me and said:

“Mo tiẹ̀ fẹ́ràn rẹ. Bí ọ̀rẹ́ rẹ (referring to my fiancée) ṣe ròyìn rẹ gẹ́lẹ́ náà la ṣe bá ẹ. Tó bá jẹ́ ẹlòmí-ìn ni, bó ṣe ń bọ̀ wáá kí wá lónìí, jàlàmíà ló máa wọ̀ ká le mọ̀ pé mùsùlùmí ni, tàbí kí ó wọ kóòtù ká le mọ̀ pé ó kàwé. Yóó sì tún máa sọ Òyìnbó díèdíẹ̀, pàápàá nígbà tó ti mọ̀ pé Èkó lòún ń bọ̀. Nítorí naa, mo rí i pé ó kì í ṣe fàwọ̀rajà tàbí alágàbàgebè ọkùnrin.”

(“In fact, I like you. You appeared exactly as your fiancée described you. If it were someone else, he would try to impress us by wearing a Muslim outfit so that we would recognize him as a devoted Muslim, knowing that we are Muslims. Or he would wear a suit so that we would assume he is educated. Also, being aware that he was coming to Lagos, he would try to code-mix instead of speaking the undiluted Yorùbá you are speaking now. That shows you are neither a hypocrite nor a pretender.”)

So, I have no regrets about being an ambassador of Yoruba culture. Although I am not a wealthy man, I thank God for making me who I am.